Christina och klassiska antikviteter

Theresa Kutasz Christensen, PhD – Art Historian specializing in provenance research and the history of collecting by women

Christina as Minerva

Falk after David Beck and Erasmus Quelinus, 1649, engraving, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, P.7095-R

Christina has long been referred to as the Minerva of the North, a title which projected onto her the Roman goddess’s positive aspects including knowledge, peace, patronage of the arts, and strength in war. It established her court in Stockholm and her Roman residences as centers for knowledge and the arts and it was a nod to the classicized public persona curated for Christina that highlighted her education, her famed collections, and her patronage. The queen’s association with Minerva was additionally used to emphasize both her country’s power in war and her establishment of peace through the treaty of Westphalia. Throughout her life, Christina was represented through a multitude of such classical allegories- or symbolic figures- that were easily transferred across media like books, parades, musical arrangements, ephemeral celebrations, feasts, prints, medals, paintings, sculptures, operas, and plays. Unlike Elizabeth I of England, another unmarried queen, Christina decided not to adopt the public image of an eternal virgin and instead embodied a timeless, borderless, image of queen of knowledge by assuming the attributes of classical heroes including Minerva, Hercules, Constantine, Apollo, Flora, and Alexander the Great. The wide variety of propagandistic, allegorical media that was commissioned by her, produced for her, or disseminated about her was part of a well-defined internationally recognized symbolic language perfectly suited to Christina’s cosmopolitan court and life outside of Sweden.

Today, Christina’s relationship with classical past is primarily known through her large and impressive collections of antiquities. The queen’s purchase and display of art in both Stockholm and Rome included ancient Greek, Roman, and Egyptian curiosities, coins, sculptures, and architectural fragments, as well as a large antiquarian library. Christina’s earliest experience of objects from the ancient Mediterranean was likely as a child, investigating small coins and sculptures in the Augsburg Cabinet, now housed in the Gustavianum in Uppsala. Once she grew up, Christina employed agents across Europe and around the Mediterranean who searched for books and objects to send back to her in Stockholm. Nicolaas Heinsius, Isaac Vossius, Michael le Blon, Mathius Palbitzki, Jeremias Falk, Spiering Silvercroon, and the Swedish commissioner in Amsterdam, Harald Appelbom, were all involved in the purchase of art, books, coins, plasters, and antiquities for Christina. It was through Heinsius and Vossius that Christina bought a significant number of her books and antique coins while Silvercroon and le Blon organized purchases in the Netherlands including the acquisition of a significant collection of antique busts from the former collection of Burgomaster Nicolaas Rockox in Antwerp. Palbitski traveled to locations such as Egypt, Turkey, and Italy making arrangements for purchases, although many of the works secured by him likely never made it to Christina.

Gonaga Cameo.

ca. 3rd century B.C.E., carved sardonyx, silver, and copper. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, ГР-12678 (Photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons)

While building her collections in Sweden, Christina received many items taken by her troops during the sack of Prague. The war booty came from local estates and the remains of Emperor Rudolph II’s collection and included many paintings and sculptures. Christina’s antiquities collection was enriched by books, coins, and reportedly even a mummy. Among the most famous items to enter her collections from Prague was the so-called Gonzaga Cameo, an antique carved gem which had previously been owned by Isabella d’Este, another famous female collector of antiquities. We cannot know the entirety of what Christina owned in Stockholm owing to the destruction of objects and records in a fire at the Tre Kronor palace in 1697 but inventories suggest that Christina owned up to 166 antique sculptures, restored fragments, or works after the antique. Only 19 busts can be identified from Christina’s Swedish collection today with the majority currently in the collections of the Nationalmuseum and displayed in Gustav III’s Museum of Antiquities. As far as we know, the majority of Christina’s antiquities in her Swedish collections were left behind, gifted, pawned, or used as payments and never made it to Rome with the rest of her collections inventoried and sent south by her curator and deputy librarian, Marquis Raphaël Trichet du Fresne.

After arriving in Rome, Christina was familiarized quickly with the city’s classical history. Her initial accommodations in the Farnese palace were still decorated with items from the family’s famous collection of antique marbles, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. After settling in the Palazzo Riario, Christina and her antiquarian Giovanni Pietro Bellori built a large library and a collection of classical sculpture. While Christina commissioned some items in her collections including an incredible 14 volume copy of Pirro Ligorio’s alphabetical manuscript on the antiquities of Rome, many of her Roman collections were built through purchases from established Roman collections. Christina did receive Papal approval to sponsor her own excavations in order to build her collections, however; these endeavors were at best of middling success.

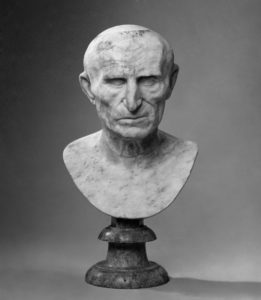

Unknown Roman- Possibly the Emperor Galba

ca. 1st c. B.C.E., marble. Nationalmuseum, Gustav III’s Museum of Antiquities, Stockholm, NMSk 87 (Photo: Nationalmuseum)

Christina’s Roman antiquities collection occupied the extensive gardens as well as 10 rooms- the entire ground floor- of the Palazzo Riario. There she displayed ancient marbles, architectural ornaments, and inscriptions in thematically designed rooms that promoted knowledge and rulership as well as her allegorical associations with figures like Apollo, Alexander the Great, and Flora. Many pieces, like her famous sculpture of Clitia by Giulio Cartari, were heavily restored ancient fragments. She also owned modern sculptures after the antique in marble and bronze by artists like Dominico Guidi, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and the workshop of Nicolas Cordier which she displayed in amongst her ancient works. In Bellori’s Nota delli musei of 1664, which outlines the major collections, libraries, and museums in Rome, Christina is one of only three women noted to own antiquities and the only woman to have such an extensive collection documented. In total, Christina’s Roman collection contained at least 208 sculptural works that were ancient or after the antique, at least 80 antique columns, and an unspecified number of architectural decorations, sculptural fragments, manuscripts, cameos, carved gems, coins, tables, basins, urns, and small bronzes.

Castor and Pollux/Orestes and Pylades or The San Ildefonso Group.

ca. 10 B.C.E., Carrara marble. Museo del Prado, Madrid, E-28 (Photo: Copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado)

Among the most well-known antique works in her Roman collection was a statue group of Castor and Pollux, now known as the San Ildefonso Group, which was mounted on a pedestal covered in antique bas-reliefs of battle. The most famous room in Christina’s palace, the sala delle muse, served occasionally as a throne room. Unlike the other ground floor rooms which were densely packed with sculptures, this room held only a group of eight seated marble muses, found in Hadrian’s villa in the 1500s, and a modern statue of Apollo. The statues ringed the room and were interspersed with classical columns erected in front of walls painted with landscapes that made visitors feel like they were inside a temple atop Mt. Parnassus in the company of Christina, Apollo, and the muses. These muses as well as the San Ildefonso group are now on display at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Following her death, Christina’s antiquities collections were purchased nearly in its entirety by Prince Livio Odescalchi. Most of Christina’s marbles were later acquired by Elizabetta Farnese and her husband Philip V of Spain through a sale from theOdescalchi in 1723-24. The sculptures decorated the royal palace of San Ildefonso at la Granja and are now owned by the Patrimonio Nacional and the Museo del Prado. Christina’s collection of coins, medals, engraved gems, and cameos were noted in the collection of the Odescalchi but were not included in the Spain sale. The majority of her library, including the copy of Ligorio’s manuscript and her collection of printed books, is now owned by the Vatican.

For Further Reading:

Primary Sources:

Bellori, Giovanni Pietro. Nota delli musei, librerie, galerie et ornamenti di statue e pitture ne’ palazzi, nelle case e ne’ giardini di Roma. Rome, 1665. Reprint, Rome: Istituto nazionale di archeologia e storia dell’arte, 1976.

Inventaire des meubles et hardes appartenants a sa Majeste la Serenissime Reyne de Suede, destines pour envoyer a Rome, reposants en ceste ville d’Anvers 1656. FelixArchiefStadsarchief Notariaat, Antwerp, no. 2479.

Wilmart, André. Analecta reginensia: extraits des manuscrits latins de la reine Christine conservés au Vatican. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca apostolica Vaticana, 1933.

Secondary Literature:

Andrén, Arvid. “Antik skulptur I svenska samlingar.” Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 1964.

Azcue Brea, Leticia. “El origen de las colecciones de escultura del Museo del Prado: El Real Museo de Pintura y Escultura.” In El Taller Europeo: Intercambios, influjos y préstamos en la escultura moderna europea, 73-110. Valladolid: Museo Nacional de Escultura, 2012.

Barba, Miguel Ángel Elvira. Las Esculturas de Cristina de Suecia: un tesoro de la Corona de España. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 2011.

Barrón, Eduardo. Catálogo de la escultura. Madrid: Imprenta y fototipia J. Lacoste, 1908.

Biermann, Veronica. “The Virtue of a King and the Desire of a Woman? Mythological Representations in the Collection of Queen Christina,” Art History 24 (2003): 213–30.

Bildt, Carl. Les Médailles Romaines de la Reine Christine de Suède. Rome: Loescher, 1908.

Boyer, Ferdinand. “Les antiques de Christine de Suède a Rome.” Revue Archeologique 35 (1932): 254-67.

Brummer, Hans Henrik. “Minerva of the North.” In Politics and Culture in the Age of Christina edited by Marie-Louise Roden, 77-92. Stockholm: Suecoromana, 1997.

Callmer, Christian. Drottning Kristinas samlingar av antik konst. Stockholm: Norstedt, 1954.

Danielsson, Arne. “Sébastien Bourdon’s equestrian portrait of queen Christina of Sweden— Addressed to ‘his Catholic Majesty’ Philip IV.” Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journal of Art History, 58:3 (2008): 95-108.

Haidenthaller, Ylva. “Pallas Nordica: Drottning Kristinas minervamedaljer.” Uppsala University Coin Cabinet Working Papers 7 (2013): 1-39.

Herrero Sanz, María Jesús, “Recorrido de la escultura clásica en el palacio de San Ildefonso a través de los inventarios reales,” El coleccionismo de escultura clásica en España. Actas del simposio. Edited by. Fernando Checa and Stephan F. Schröder, 239-258. Madrid, Museo del Prado, 2002.

Iiro, Kajanto. Christina Heroina: Mythological and historical exemplification in the Latin panegyrics on Christina Queen of Sweden. Helsinki: 1993.

Inventory, Spain 1747- Inventory of Elizabeth Farnese at la Granja. Madrid: Archivo General de Palacio, San Ildefonso, I-3.

Kutasz Christensen, Theresa. “Regina Christina, Antiquario: Queen Christina of Sweden’s Development of a Classical Persona Through Allegory and Antiquarian Collecting.” PhD dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 2018.

Leander Touati, Anne-Marie. Ancient Sculptures in the Royal Museum, the eighteenth-century collection in Stockholm. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1998.

Leander Touati, Ann-Marie and Johan Flemberg. Gustav III’s Museum of Antiquities. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2013.

Lichtenstein Museum. Samson and Delilah a Rubens Painting Returns. Milan: Skira, 2007.

Museo del Prado. Cristina de Suecia en el Museo del Prado, cat. exp. Madrid, Museo del Prado, 1997.

Sjøvoll, Therese. “Queen Christina of Sweden´s Musaeum: Collecting and Display in the Palazzo Riario.” PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 2015.

von Platen, Magnus, ed. Queen Christina of Sweden Documents and Studies. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1966. (of particular note for this topic are the essays by Bignami Odier, Callmer, Gustafsson, Karling, Masson, Neumann, Rasmusson, Steneberg, and Stephan.)

Walker, Stephanie. “The Sculpture Gallery of Prince Livio Odescalchi,” The History of Collections 6, no.2 (January 1994): 189-219.

Zirpolo, Lilian. “Severed Torsos and Metaphorical Transformations: Christina of Sweden’s Sale delle Muse and Clytie in the Palazzo Riario‐Corsini.” Aurora, The Journal of the History of Art (2008): 29-53.

Images:

Christina as Minerva

Falk after David Beck and Erasmus Quelinus, 1649, engraving, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, P.7095-R (Photo: http://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/133914)

Unknown Roman- Possibly the Emperor Galba

ca. 1st c. B.C.E., marble. Nationalmuseum, Gustav III’s Museum of Antiquities, Stockholm, NMSk 87 (Photo: Nationalmuseum) http://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=33258&viewType=detailView

Gonaga Cameo.

ca. 3rd century B.C.E., carved sardonyx, silver, and copper. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, ГР-12678 (Photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons)

Castor and Pollux/Orestes and Pylades or The San Ildefonso Group.

ca. 10 B.C.E., Carrara marble. Museo del Prado, Madrid, E-28 (Photo: Copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado)

Theresa Kutasz Christensen, PhD – Art Historian specializing in provenance research and the history of collecting by women TKutaszChristensen@gmail.com